The first meat conference I attended gave me a sense of connection - to broader conversations about food systems, to the particular local concerns of the Rockies and the Plains, and to other individuals who work all along the meat supply chain. The Carolina Meat Conference has been going since 2011 and inspired the Mountain Meat Summit, among other regional gatherings. Riding high on the thin mountain air and packed schedule of farm tours and speakers, I registered for the Carolina Meat Conference from my Bozeman hotel room and marked off the last week in July on my calendar.

Here are some notes from my trip to Boone, NC for the conference:

This conference is big. I rolled up at the Appalachian State University campus around 5pm on Monday, the day before the conference started. I had selected the economic option - staying in the dorms. I felt like I was dropping myself off at summer camp (or summer school…) as I hauled the chic powder blue sateen duvet, snagged off my guest bedroom and stuffed unceremoniously into my car’s backseat (I’d driven to Boone from Chicago over two days), across the linoleum tiled dorm lobby, into the elevator to the fifth floor and finally to my painted cinderblock walled dorm room. It was hard to grasp the scale of the event that first night, though I ran into some other attendees in the ladies’ room and the lobby, picking up ID cards and keys. It wasn’t until the morning keynote that I learned there were over 600 people in attendance, taking over the mostly deserted campus for two days of near-continuous programming.

Dr. Temple Grandin, meat world’s Taylor Swift? My first Temple Grandin sighting was a classic stop-in-your-tracks double take. I’d seen her name on the bill, but her presence was more impactful than I expected, even though she was simply walking into the student center at the start of the day, past a display of her books. I wasn’t the only one affected. She turned heads everywhere she went, going always with a purposeful stride, her gray finger waves visible above the crowds in the hallway where the vendors had their booths selling cattle feed supplements derived from algae, or Spanish-language resources for slaughterhouse employers, and in the busy cafeteria where cliques inevitably formed at each lunchtime. I got to see a lot of Dr. Grandin over the course of the two days, including at her rousing keynote speech, which dispensed with preamble to dive right into a mini-intensive on humane animal handling and the state of the industry, delivered in short, clear statements and punctuated with amusing slides and audience participation drills. What struck me most about Dr. Grandin’s perspective is her understanding of scale. Much of her career has focused on the big guys - JBS, McDonald’s. Throughout the conference I heard her repeat, “Big isn’t bad, it’s fragile.” This is a both a refreshing and a challenging concept to deliver to a group of 600 people who generally align with the “niche” side of the meat industry, aka, the small guys. In these circles, scale frequently takes on a moral tone, where big is bad and small is both cast as victim and elevated as our salvation. Her keynote and her commentary subtly dismantled this dichotomy, foregrounding animal welfare and functional systems that feed people above all else. A slaughter demonstration which she attended and commented on underlined this point (another note on that later).

Not in Kansas anymore. The opening keynote of the conference featured local NC celebrity, former WRAL- TV meteorologist Greg Fishel, who shared his personal journey from joining the weather biz as an ambitious young conservative in the 80s, deeply skeptical of climate change, to becoming a vocal proponent of looking hard at the facts and taking action to prepare in our reality where the climate is already changing. Beyond the personal history, Fishel’s talk was a discussion of the science behind humankind’s impact on the climate, complete with graphs, a brief scientific explanation of the reflective properties of carbon dioxide, and an emphasis on how easily studies and statistics can be manipulated out of context. He began his talk with a plea for open minded consideration, followed by a wink and a laugh, saying even if you don’t agree what I’m about to say, be civil and we can all walk out of this room as friends! He went on to deliver a point by point rebuttal to the suspicious layman, an attempt at discreet persuasion to look at the facts with fresh eyes, all with the confidence and charisma of a man who made his career on public television.

I hadn’t yet had a chance to absorb my surroundings or converse with other attendees, local or otherwise, so it wasn’t until later that day at the big Argentine grill-out the conference hosted that I was able to get a sense of how Fishel’s talk was received. I sat at a long table under a rental tent pitched against the looming threat of rain, among a group that included a several small-scale farmers/homesteaders and some agricultural extension specialists from a nearby university. Some were colleagues, part of the local scene; others, myself included, were total strangers. Relishing the pulled pork and smokey short rib on my paper plate, I listened to them talk shop - administration at the university, recent cruise vacations, best local options for chicken processing - til I suddenly became aware that the keynote speech was on the table and under scrutiny. One voice confidently grounded itself in faith and seemed to waive Fishel’s warning off, categorizing it as something beyond human control and machinations. Another sited the vast expanse of time, claiming it was doubtful humans could make such a difference in a short period (a point Fishel had addressed directly, but this attendee had been working at her farm that morning and missed the keynote). Another voice pulled subtly towards the middle, breaking tension with a joke about the weather. The conversation was lively but not heated. When I chimed in, the only voice without any measure of soothing southern drawl, to say that however dubious we are of climate change we still have choices to make every day, so we might as well make the choices that help conserve and replenish resources, I was listened to intently. Based on their shop talk, I knew that each of these people was involved in making agriculture more sustainable and improving their communities’ access to local food on a daily basis. A broad acceptance of climate change just doesn’t seem to be the thing motivating them. I took this as a reminder that while guilt and dread might be effective catalysts for changing individual behavior, deeper, lasting change tends to come from people acting to preserve and protect what’s closest to them - their health, their financial security, their homes, their traditions. When communities share these interests, you could have a movement on your hands.

Catering by Live Fire Feasts. Mobile slaughter is an important innovation with specific challenges. I was hastily reviewing the conference website days before I embarked on the drive down to North Carolina, taking note of sessions I didn’t want to miss and googling restaurants and local attractions in Boone. Buried in the middle of the first day was a listing that read, “Small Ruminant Mobile Processing Unit Workshop” hosted by Shipley Farms and attended by Dr. Temple Grandin. I scrolled to the right and was met with the words “SOLD OUT.” I was so crestfallen that I toyed with skipping the conference all together, asking myself - how did I miss this??? Happily I still made the drive, and I got lucky - someone was unable to make it, and there was room in the van.

I was hellbent on attending this session not only because my favorite meat celebrity would be in attendance, but because bottlenecks and innovations around slaughter (processing) infrastructure have captured my attention over the past couple years. As a butcher, most of my experience in the industry has been working with meat, not with animals. Farmers and ranchers are often on the opposite end, dealing with animals but rarely with meat. At the processing level, you have to understand and respect both the living creature and the food as you manage the transition from animal to meat. When people ask me what makes meat taste good, I’ve been more and more focused on the processing, from slaughter through carcass dry aging, not that it is more important than the months and years a farmer spends raising the animal or the technical work the butcher does to translate the carcass into cookable cuts, but as the invisible link between the two. The more I’ve gotten to witness and learn about that crucial step, the more I’ve felt compelled to share what I’ve learned with my students, friends, and consumers more broadly.

Four sheep were gathered in a small pen beneath a sun shade on the valley floor of Shipley Farms cattle ranch, next to a shiny white cargo trailer, which VSU agricultural extension specialist Dr. Dahlia O’Brien and her team worked for years to get funded, built, and complaint as a Mobile Processing Unit. The program is both a feasibility study for MPUs as well as a functioning unit aiming to serve the region. The unit is set up for inspection by the state and/or the federal authorities wherever it goes, providing a convenient processing option for small-scale farmers who are far from brick and mortar processing facilities.

Davida Rimm-Kaufman, the unit coordinator, got into the pen to isolate one of the rams (rambunctious, in-tact male sheep) donated by a local farmer. “Sheep don’t like to be alone!” stressed Dr. Grandin from her own sun-shaded perch, as our small group watched the ram jump and spin to avoid Davida and rejoin its companions. With the advantage of mobility, MPU’s also face the challenge of responding and adapting to each site, from terrain, to water and electricity access, to animal handling. In brick and mortar slaughterhouses, farmers deliver their animals to pens where they have shade, water, and feed as needed (this is called lairage, a word I learned on this trip). These pens, hopefully, have a humane and functional system to get individual animals into the chute, where they are calm but immobile, and a swift knock to the head with a captive bolt gun (or electrical shock as the case may be for smaller animals) renders them unconscious. Though we may shudder at the number of animals a mega-plant can process in day, just as we do at the crowded feedlots where they spend their final months, many of these plants have extensively engineered animal handling systems using Dr. Grandin’s concepts and designs. If you’re pulling an MPU up to a farmers backyard, you’re going to have to create an animal handling system from scratch, or you’ll be chasing animals around all day, stressing them (and you) out. Davida and Dahlia were able to subdue and knock the ram in relatively short order, but even the five minutes of tussle were enough to underline this point and leave Davida sweating in the July sun with mud on knees of her jeans.

To this end, Dr. Grandin and Dr. O’Brien addressed the option of ports or docking stations for MPU’s, which would be permanent but easy and cheap to set up, and would take care of questions like water access (critical for cleaning the unit and caring for animals), electrical needs (generators are loud and not perfectly reliable), and animal handling needs, such as pens implementing Dr. Grandin’s designs for humanely and easily moving animals where you want them to go. While this undercuts the mobility of MPU’s to some extent, it solves for some of MPU’s thornier issues, and could create more regional hubs for inspected slaughter. Some farmers would still have to travel, but access would be greatly improved for a fraction of the cost of building local networks of small brick and mortar processing plants.

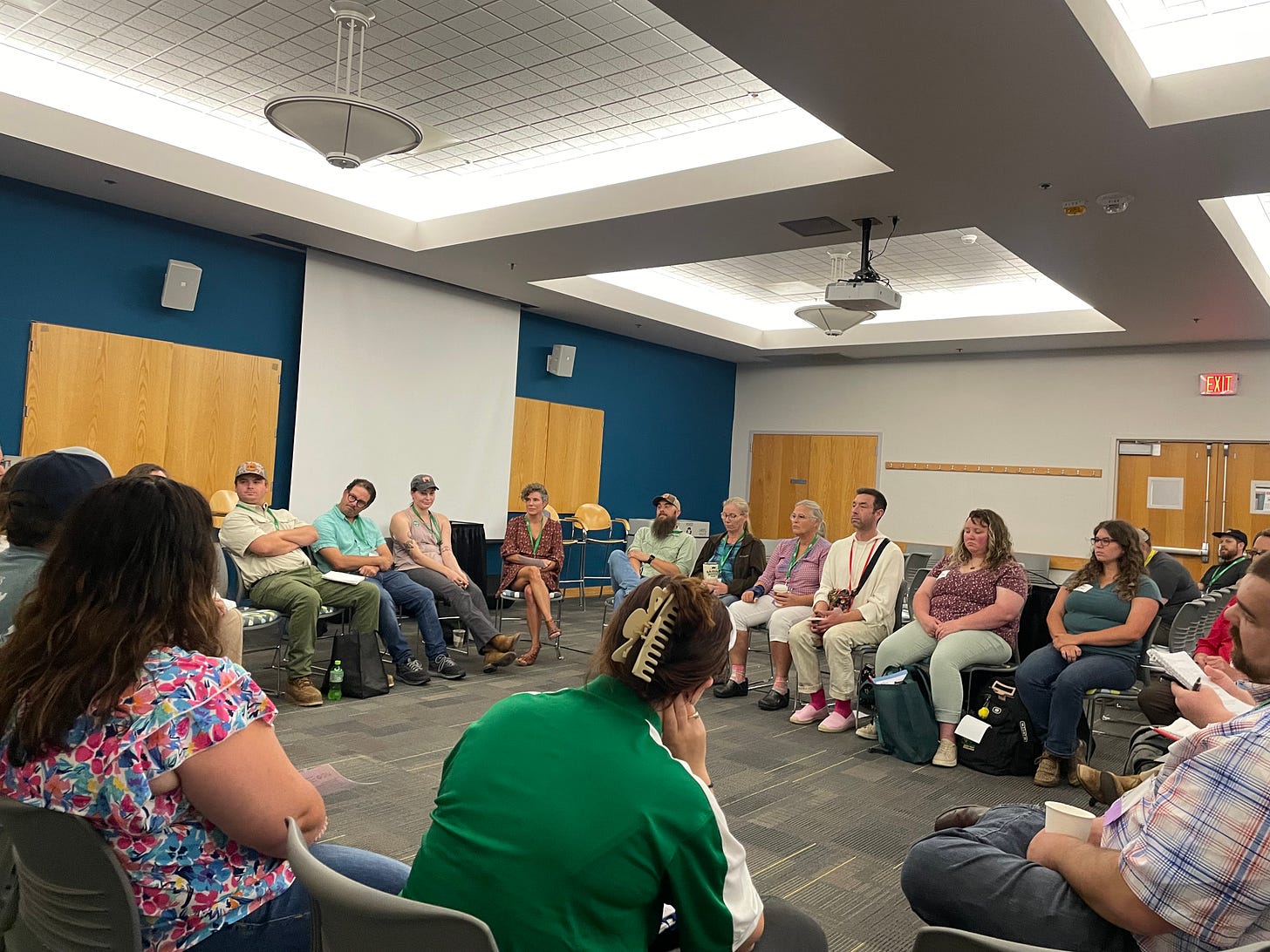

How do we train the next generation of butchers? Labor shortage is a commonly sited issue plaguing meat processors. As I touched on in the notes from the Mountain Meat Summit, with many of these smaller regional plants being in somewhat remote or rural areas with limited housing availability and thin populations, it’s hard to attract a consistent supply of workers. Rebecca Thistlewaite of Niche Meat Processors of North America (NMPAN) hosted the panel “Developing a Future Workforce for Local Meats,” and it was the highlight of the conference panels for me. Rather than lecturing from the front of the classroom, she arranged the 30 or so who people showed up in a tight circle, and had us all introduce ourselves. From there, she moderated as the group of butchers, ranchers, extension specialists, processing plant managers, and people from the non-profit sector chimed in to share their experiences, frustrations, and visions for the path ahead.

We heard about a young woman’s experience working in a processing plant right out of high school. It was a job she loved, and one she’s interested in getting back into, but her peers had negative associations with slaughterhouses and were confused and even derisive when she shared that she worked in one, an experience that felt lonely and alienating. One response to this was that the industry suffers from an image problem, that we need to find a way to make butchery sexy again (hopefully not in the mustached/knife-tattooed hipster way that was briefly cool in the first decade of the 2000s). We talked about progress that could be made in slaughterhouses themselves, from improvements in pay, profit sharing, open-book management where key metrics are shared with employees, and cross-training, to more thoughtfully laid out spaces, ones with windows, clean white paint, a cheerier built environment. The lack of unions as well as the lack of US department of labor apprenticeships came up, another reminder that for the most part in our food system (at the big, conveyor belt plants that dominate the industry), butchery is not skilled labor - it’s for a workforce seen as interchangeable and nearly disposable, without degrees, certificates, or even documentation as citizens, a reality that came to fruition in the second half of the 19th century and is still with us today.

Re-skilling this “de-skilled” role is necessary for the functioning of a more localized, rather than centralized, food system. This is part of the picture of why local meat is more expensive than commodity meat - if we pay the farmers more and pay the butchers more, the cost of meat will go up. Buying options like meat shares and CSA’s can offer value, but they can’t compete with a system that exploits both its producers and its workforce. This reality is frequently acknowledged, but I’ve yet to be in a room where food access and equality and making ranching or small scale meat processing more profitable are being championed at the same volume. To be fair, I chose to come to this panel whose focus was explicitly on the future workforce of small meat plants. There was a concurrent session, “Sales Strategy and Food Sovereignty,” that I wanted to attend as well, but that’s one of the drawbacks of such a big conference, where six talks, panels, or demonstrations compete for participants’ attention at each hourly slot.

The impossibly packed conference schedule mirrors the way something as simple as a steak touches so many different aspects of human life, knowledge, and culture. I left the conference with a head full of new connections, a list of organizations to check out, several job offers from local North Carolina meat processing plants (also short on labor and thrilled to meet a butcher!), and an appreciation for the vast and varied expertise of the panelists, organizers, and attendees. As always, I’m chewing my way through some of these issues on a local level, offering butchery classes, organizing farm and producer tours, selling meat shares, and donating to my local food pantry. Stay tuned for more musings!

Mccllough, I appreciated the way you chronicled your trip; putting us right there at the University. It's exciting to learn the focus on improving butchery from a more positive work environment, supporting the local meat farmers and putting the "humane" perspective to this skill that is more often overlooked. Thank you. Jean Kusnir (Gustavsen)

I love this piece because it encompasses the whole process of farm to table. And also, I love that you got to see Temple Grandin and hear her speak!